Lakota people

|

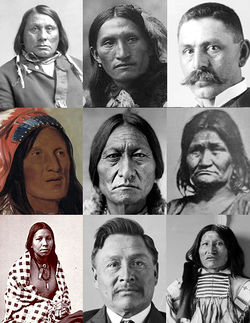

| Lakota portraits |

| Total population |

|---|

| 55,000 on Lakota on reservations, 103,255 Sioux on census[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

( |

| Languages |

|

Lakota, English |

| Religion |

|

traditional tribal religion, Sun Dance, |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

other members of Oceti Sakohowin (Santee, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Yankton, Yanktonai)[2] |

The Lakota (pronounced [laˈkˣota]; also known as Lakȟóta, Teton, Tetonwan, Teton Sioux) are a Native American tribe. They are part of a confederation of seven related Sioux tribes (the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ or seven council fires) and speak Lakȟóta, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language.

The Lakota are the western-most of the three Sioux-language groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota. The seven bands or "sub-tribes" of the Lakota are:

- Sičháŋǧu (a.k.a. Brulé, Burned Thighs)

- Oglála (a.k.a. Scatters thier own)

- Itázipčho (a.k.a. Sans Arc, No Bows)

- Húŋkpapȟa

- Mnikȟówožu (a.k.a. Miniconjou)

- Sihásapa (a.k.a. Blackfoot Sioux)

- Oóhenuŋpa (a.k.a. Two Kettles)

Notable persons include Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull) from the Hunkpapa band; and Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse), Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud), Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk), Billy Mills and Touch the Clouds from the Oglala band.

Contents |

History

The Lakota were originally referred to as the Dakota when they lived by the Great Lakes. Encroaching European-American settlement led them to migrate west from the Great Lakes region. They later called themselves the Lakota, and were also called Sioux. They were introduced to horse culture by the Cheyenne about 1730.[3]

After their adoption of the horse, šúŋkawakȟáŋ ([ˈʃũka waˈkˣã]) ('dog [of] power/mystery/wonder') their society centered on the buffalo hunt with the horse. There were estimated to be 20,000 Lakota in the mid-18th century. The number has now increased to about 70,000, of whom about 20,500 speak the Lakota language[4].

After 1720, the Lakota branch of the Seven Council Fires split into two major sects, the Saône who moved to the Lake Traverse area on the South Dakota–North Dakota–Minnesota border, and the Oglala-Sicangu who occupied the James River valley. By about 1750, however, the Saône had moved to the east bank of the Missouri River, followed 10 years later by the Oglala and Brulé (Sičangu).

The large and powerful Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages had prevented the Lakota from crossing the Missouri for an extended period. Smallpox and other infectious diseases nearly destroyed these tribes, the way was open for the first Lakota to cross the Missouri into the drier, short-grass prairies of the High Plains. These Saône, well-mounted and increasingly confident, spread out quickly. In 1765, a Saône exploring and raiding party led by Chief Standing Bear discovered the Black Hills (which they call the Paha Sapa), first the territory of the Cheyenne. Just a decade later, in 1775, the Oglala and Brulé also crossed the river. The great smallpox epidemic of 1772–1780 destroyed three-quarters of the American Indian populations in the Missouri Valley. In 1776, the Lakota defeated the Cheyenne, as the Cheyenne had earlier defeated the Kiowa. The Cheyenne moved west into the Powder River Country[3], and the Lakota gained control of the land which became the center of the Lakota universe.

Initial contacts between the Lakota and the United States, during the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806 was marked by a standoff. When Lakota bands refused to allow the explorers to continue upstream, the Expedition prepared to do battle.[5] More than half a century later, after US forces built Fort Laramie on Lakota land, officials negotiated the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 with the Lakota and other numerous Plains tribes to protect emigrant travelers on the Oregon Trail, which crossed their territory. The Cheyenne and Lakota had raided emigrant parties in part due to competition for resources, and because of settler encroachment on their lands.[6] Formally, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 acknowledged native sovereignty over the Great Plains in exchange for free passage along the Oregon Trail, for "as long as the river flows and the eagle flies".

The government could not enforce the treaty against European-American encroachment. When the Lakota and other bands attacked settlers and emigrant trains, there was public pressure for the US Army to punish the tribes. In Nebraska on September 3, 1855, 700 soldiers under American General William S. Harney avenged the Grattan Massacre by attacking a Lakota village, killing 100 men, women, and children. Other wars followed; and in 1862–1864, as refugees from the "Dakota War of 1862" in Minnesota fled west to their allies in Montana and Dakota Territory. With increasing settler expansion, war found the tribes again.

Because the Black Hills are sacred to the Lakota, they objected to mining in the area, which had been attempted since the early years of the 19th century. In 1868, the U.S. government signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, exempting the Black Hills from all white settlement forever. 'Forever' lasted only four years; when gold was publicly discovered there, an influx of prospectors descended upon the area.

Again, the US reacted to attacks on settlers and miners with military force, abetted by army commanders such as like Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer. The latter tried to administer a lesson of noninterference with white policies, resulting in the Great Sioux War of 1876-77. General Philip Sheridan encouraged troops to hunt and kill buffalo as a means of "destroying the Indians' commissary."[7]

The unified Northern Cheyenne led much of the warfare after 1860 on the Plains, along with allied Lakota and Arapaho bands, which operated independently. They defeated General George Crook's army at the Battle of the Rosebud, and a week later defeated the U.S. 7th Cavalry in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Custer attacked a camp of several tribes, much larger than he realized. Their combined forces killed 258 soldiers, wiping out the entire Custer battalion, and inflicting more than 50% casualties on the regiment.

Their victory over the U.S. Army would not last, however. The US Congress authorized funds to expand the army by 2500 men. The reinforced US Army defeated the Lakota bands in a series of battles, finally ending the Great Sioux War in 1877. The Lakota were eventually confined onto reservations, prevented from hunting buffalo and forced to accept government food distribution.

In 1877 some of the Lakota bands signed a treaty ceding the Black Hills to the United States. Low-intensity conflicts continued. Fourteen years later, Sitting Bull was killed at Standing Rock reservation on December 15, 1890. The US Army attacked Oglala Lakota in the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890 at Pine Ridge.

Today, the Lakota are found mostly in the five reservations of western South Dakota: Rosebud Indian Reservation (home of the Upper Sičangu or Brulé), Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (home of the Oglala), Lower Brule Indian Reservation (home of the Lower Sičangu), Cheyenne River Indian Reservation (home of several other of the seven Lakota bands, including the Sihasapa and Hunkpapa), and Standing Rock Indian Reservation, also home to people from many bands. Lakota also live on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana, the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation of northwestern North Dakota, and several small reserves in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Their ancestors fled to "Grandmother's [i.e. Queen Victoria's] Land" (Canada) during the Minnesota or Black Hills War.

Large numbers of Lakota live in Rapid City and other towns in the Black Hills, and in metro Denver. Lakota elders joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) to seek protection and recognition for their cultural and land rights.

Government

Legally[8] and by treaty a semi-autonomous "nation" within the United States, the Lakota Sioux are represented locally by officials elected to councils for the several reservations and communities in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and also in Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada. They are represented on the state and national level by the elected officials from the political districts of their respective states and Congressional Districts.[9] Band or reservation members living both on and off the individual reservations are eligible to vote in periodic elections for that reservation. Each reservation has a unique local government style and election cycle based on its own constitution[10][11] or articles of incorporation. Most follow a multi-member tribal council model with a chairman or president elected directly by the voters.

- The current President of the Oglala Sioux, the majority tribe of the Lakota located primarily on the Pine Ridge reservation, is Theresa Two Bulls.

- The President of the Sicangu Lakota at the Rosebud reservation is Rodney M. Bordeaux.

- The Chairman of the Standing Rock reservation, which includes peoples from several Lakota subgroups including the Hunkpapa, is Charles W. Murphy.

- The Chairman of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe at the Cheyenne River reservation, comprising the Mniconjou, Izipaco, Siha Sapa, and Ooinunpa bands of the Lakota, is Joe Brings Plenty, Sr.

- The Chairman of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, which is home to the Lower Sicangu Lakota, is Michael Jandreau.

Tribal governments have significant leeway, as semi-autonomous political entities, in deviating from state law (e.g. Indian gaming.) They are ultimately subject to supervisory oversight by the United States Congress[8] and executive regulation through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The nature and legitimacy of those relationships continue to be a matter of dispute.[12]

Independence movement

Beginning in 1974, some Lakota activists have taken steps to become independent from the United States, in an attempt to form their own fully independent nation. These steps have included drafting their own "declaration of continuing independence" and using Constitutional and International Law to solidify their legal standing.

A 1980 U.S. Supreme Court decision awarded $122 million to eight bands of Sioux Indians as compensation for land claims, but the court did not award land. The Lakota have refused the settlement.[13]

In September 2007, the United Nations passed a non-binding Resolution on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand refused to sign.[14]

On December 20, 2007, a group of Lakota under the name Lakota Freedom Delegation traveled to Washington D.C. to announce a withdrawal of the Lakota Sioux from all treaties with the United States government.[15]. These activists had no standing under any elected BIA tribal government. The group claimed official standing under the traditional Lakota Treaty Councils, representing the traditional Tiospayes (matriarchal family units). These have been the traditional form of Lakota governance.

Longtime political activist Russell Means said, "We have 33 treaties with the United States that they have not lived by." He was part of the delegation's declaring the Lakota a sovereign nation with property rights over thousands of square miles in South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming and Montana.[16] The group stated that they do not act for or represent the tribal governments set up by the BIA or those Lakota who support the BIA system of government.[17]

The Lakota Freedom Delegation did not include any elected leaders from any of the tribes. Russell Means had previously run for president of the Oglala Sioux tribe and twice been defeated. Several elected BIA tribal governments issued statements distancing themselves from the independence declaration, with some saying they were watching the independent movement closely.[18] Although some Indigenous nations and groups around the world made statements in support, no elected Lakota tribal governments endorsed the declaration.

In January 2008, the Lakota Freedom Delegation split into two groups. One group was led by Canupa Gluha Mani (Duane Martin Sr.). He is a leader of Cante Tenza, the traditional Strongheart Warrior Society, that has included leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. This group is called Lakota Oyate. The other group is called the "Republic of Lakotah" and is led by Russell Means. In December 2008, Lakota Oyate received the support and standing of the traditional treaty council of the Oglala Tiospayes.

Ethnonyms

The name Lakota comes from the Lakota autonym, Lakȟóta "feeling affection, friendly, united, allied". The early French historic documents did not distinguish a separate Teton division, instead grouping them with other "Sioux of the West", Santee and Yankton bands.

The names Teton and Tetuwan come from the Lakota name thíthuŋwaŋ [ˈtʰitʰũwã], the meaning of which is obscure. This term was used to refer to the Lakota by non-Lakota Sioux groups. Other derivations include: ti tanka, Tintonyanyan, Titon, Tintonha, Thintohas, Tinthenha, Tinton, Thuntotas, Tintones, Tintoner, Tintinhos, Ten-ton-ha, Thinthonha, Tinthonha, Tentouha, Tintonwans, Tindaw, Tinthow, Atintons, Anthontans, Atentons, Atintans, Atrutons, Titoba, Tetongues, Teton Sioux, Teeton, Ti toan, Teetwawn, Teetwans, Ti-t’-wawn, Ti-twans, Tit’wan, Tetans, Tieton, and Teetonwan.

Early French sources call the Lakota Sioux with an additional modifier, such as Scioux of the West, West Schious, Sioux des prairies, Sioux occidentaux, Sioux of the Meadows, Nadooessis of the Plains, Prairie Indians, Sioux of the Plain, Maskoutens-Nadouessians, Mascouteins Nadouessi, and Sioux nomades.

Today many of the tribes continue to officially call themselves Sioux. In the 19th and 20th centuries, this was the name which the US government applied to all Dakota/Lakota people. However, some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sičangu Oyate (Brulé Nation), and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternate English spelling of Ogallala is deprecated, even though it is closer to the correct pronunciation.) The Lakota have names for their own subdivisions. The Lakota also are Western of the three Sioux groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

Notable Lakota

- Arthur Amiotte, Oglala artist, educator, curator, and author

- Black Elk (Heȟáka Sápa)

- Mary Brave Bird, Brulé author

- Nathan Chasing His Horse, actor, medicine man

- Chris Chavis (Tȟatȟáŋka), WWE wrestler

- Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó)

- Lame Deer (Tȟáȟča Hušté), Heyoka

- Kevin Locke (Tȟokéya Inážiŋ), Hunkpapa hoop dancer and flute player

- Billy Mills, Oglala Olympic Gold Medalist

- Rain-in-the-Face (Ité Omáǧažu), Hunkpapa war chief who fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn

- Red Cloud (Maȟpíya Lúta)

- Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake), Hunkpapa chief

- Michael Spears, Lower Brulé actor

- Eddie Spears, Lower Brulé actor

- Moses Stranger Horse, Brulé artist

- Touch the Clouds (Maȟpíya Ičaȟtagye)

- John Two-Hawks, musician

Reservations

Today, one half of all enrolled Sioux live off the Reservation.

Lakota reservations recognized by the U.S. government include:

- Oglala (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation)

- Sicangu (Rosebud Indian Reservation)

- Hunkpapa (Standing Rock Reservation)

- Mniconjou (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Izipaco (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Siha Sapa (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Ooinunpa (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

Some Lakota also live on other Sioux reservations in eastern South Dakota, Minnesota, and Nebraska:

- Santee Indian Reservation, in Nebraska

- Crow Creek Indian Reservation in Central South Dakota

- Yankton Indian Reservation in Central South Dakota

- Flandreau Indian Reservation in Eastern South Dakota

- Lake Traverse Indian Reservation in Northeastern South Dakota and Southeastern North Dakota

- Lower Sioux Indian Reservation in Minnesota

- Upper Sioux Indian Reservation in Minnesota

- Shakopee-Mdewakanton Indian Reservation in Minnesota

- Prairie Island Indian Reservation in Minnesota

In addition several Lakota live on Wood Mountain Indian Reserve often Wood Mountain First Nation northwest of Wood Mountain Post now a Saskatchewan historic site.

See also

- Lakota language

- Lakota mythology

- Native American tribes in Nebraska

Notes

- ↑ As of 1990. Pritzker, 329

- ↑ Pritzker, 328

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Liberty, Dr. Margot. "Cheyenne Primacy: The Tribes' Perspective As Opposed To That Of The United States Army; A Possible Alternative To "The Great Sioux War Of 1876". Friends of the Little Bighorn. http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/cheyenneprimacy.htm. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ↑ http://factfinder.census.gov/

- ↑ The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, University of Nebraska.

- ↑ Brown, Dee (1950) Bury My Heart at Wounded KneeMacmillan ISBN 0805066691, 9780805066692

- ↑ Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life, (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1999), 141.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The Indian Reorganization Act

- ↑ Indianz.Com > News > Oglala Sioux Tribe inaugurates Cecilia Fire Thunder

- ↑ Official Site of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe

- ↑ Our Constitution & By-Laws

- ↑ Indian Country Diaries . History | PBS

- ↑ "Race: The Price of Penance". Time. May 8, 1989. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,957595,00.html?promoid=googlep. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ↑ ReaderRant: UBB Error

- ↑ "Descendants of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse break away from US", Agence France-Presse news

- ↑ Bill Harlan, "Lakota group secedes from U.S.", Rapid City Journal, December 20, 2007.

- ↑ "Lakota group pushes for new nation", Argus Leader, Washington Bureau, December 20, 2007

- ↑ "Lakota Sioux have NOT withdrawn from the US", DailyKOS

- ↑ Crash, Tom. "Oglala Lakota College opens their summer artist series ". Lakota Times. 12 June 2008 (retrieved 21 Dec 2009)

References

- Christafferson, Dennis M. (2001). Sioux, 1930–2000. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 821–839). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001a). Sioux until 1850. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718–760). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001b). Teton. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 794–820). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Hein, David (Advent 2002). "Episcopalianism among the Lakota / Dakota Indians of South Dakota." The Historiographer, vol. 40, pp. 14–16. [The Historiographer is a publication of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church and the National Episcopal Historians and Archivists.]

- Hein, David (1997). "Christianity and Traditional Lakota / Dakota Spirituality: A Jamesian Interpretation." The McNeese Review, vol. 35, pp. 128–38.

- Matson, William and Frethem, Mark (2006). Producers. "The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree". The Crazy Horse family tells their oral history and with explanations of Lakota spirituality and culture on DVD. (Publisher is Reelcontact.com)

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). The Siouan languages. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400 5.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771.

- Ullrich, Jan. New Lakota Dictionary. (Lakota Language Consortium). ISBN 0-9761082-9-1. (The most comprehensive dictionary of the language, the only dictionary reliable in terms of spelling and defining words). Available at http://www.lakhota.org/html/DictionaryPrint.html

External links

- The Official Lakota Language Forum

- Dakota Blues: The History of The Great Sioux Nation

- Lakota Freedom Delegation, Lakota Oyate Group

- Lakota Freedom Delegation, Republic of Lakotah Group

- Lakota declaration of independence and related documents

- Lakota Language Consortium

- Lakota Freedom Delegation to Withdraw from Treaties in DC 2007/12/14

- The Lakota Sioux Indians Declare Independence, Ibrahim Sediyani

- The Teton Sioux (Edward S. Curtis)

- Lakota Winter Counts a Smithsonian exhibit of the annual icon chosen to represent the major event of the past year

- Official Website-Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe